The ironstone mine at Esk Valley near Grosmont has recently been opened for public access, with an accessible track leading from the Rail Trail. This has been made possible through funding from the Land of Iron project, supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund and by kind arrangement with Mulgrave Estate.

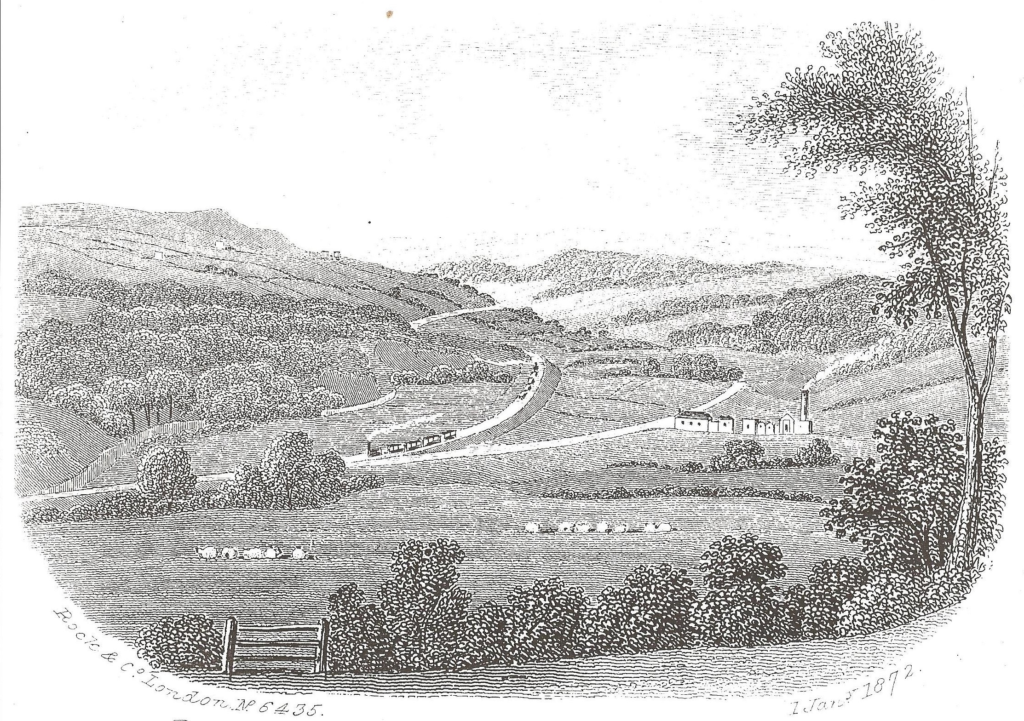

The land originally belonged to Egton Estate and in the mid 1850’s the Elwes family offered portions of their land for investors to lease for the mining of ironstone. In 1858 The Esk Valley Iron Company issued a prospectus to interested investors for a 63 year lease, the manager was Thomas Watson. It was thought, that although in the Murk Esk Valley, the name would sell more shares. A siding was put in from the Whitby and Pickering railway, to bring sandstone and bricks for the engine house and shaft and to remove the ironstone. Originally the plan was to build two blast furnaces adjacent to the railway siding in the nearby fields but this did not materialise so presumably the stone would have been shipped from Whitby to furnaces along the Tyne.

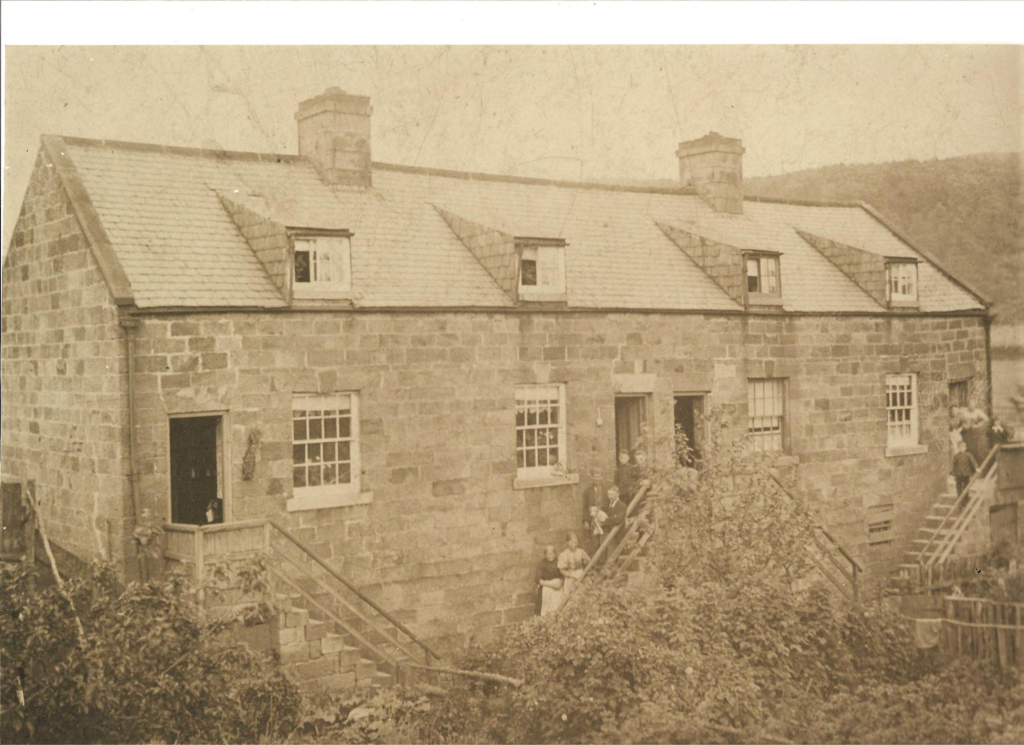

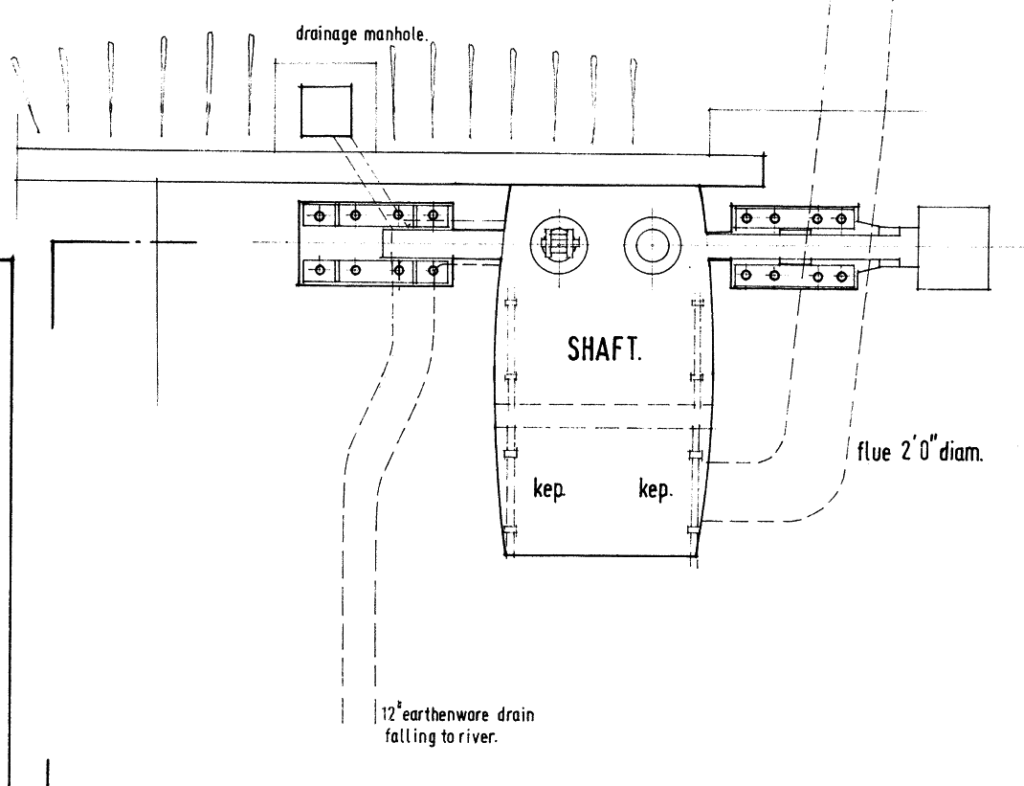

The Esk Valley Iron Company only operated for a few years, reaching the pecten level first, at 32 fathoms and the avicula, 36 fathoms, by 1862. Although the shaft sinking was progressing, the engine at 14 strokes per minute had not lowered the water much. The seam was only three feet high, with a foot of shale in the roof, in places more like two feet. Samuel Hunt managed the sinking of the shaft, he also was the go to man at Commondale, Warren Moor, Kildale and the shafts around Glaisdale furnaces. A blacksmith and joiners shop adjoined the site with room for four families on the top floors, one if which Samuel lived in. Miners lodged locally.

Financially the mine at Esk Valley was not a success; the railway had not been paid for siding access by 1862 and the rent was reduced to 5d per 22 ½ cwts, with the added cost of £600 rent if the furnaces were not built. The company persuaded a Shropshire Ironmaster William Watkin to invest £9,150 in shares and build a furnace capable of producing 100 tons of iron a week, in exchange for a role as General Manager. By 1873 the company went into liquidation, upon the death of William Watkin four years earlier, although his executors did try to re-negotiate a new lease.

The mine was to be worked longwall, unusual for this area, with ‘a place driven in 21 feet wide and then the face taken right away, 60 to 80 yards between roads’ The men were paid 22s 6d for the 21 foot place. Still the seam of ironstone was little more than 3’ 8” high.’

In the meantime the Foster family took over the Egton Estate and at Glaisdale blast furnaces had been built, with the ironstone mines on site proving to be a poor supply. The first company at Glaisdale furnaces struggled for six years and by 1872 a new firm, The South Cleveland Ironworks Limited, took over the furnaces and leased the mine at Esk Valley

In 1871 James George Beckton, a civil engineer of Whitby, wrote a report about the mine and its prospects. On the back of this the South Cleveland advertised their shares value at £200,000, even though the company only needed £60,000 to complete the works. The question was asked if the intention was to pay dividends out of capital, since much more was being requested in the share issue than was needed.

The new company built the mine managers house, Thomas Evan’s by this time, and a row of 24 cottages, less than the original 75 planned. Surprisingly most of the people who moved in were from the local villages but some experienced miners did come from Redruth, Stafford, Shropshire and Norfolk. It had become law to have a second means of exit for mines, so a new circular shaft was sunk, lined with brick.

Things didn’t go well for the South Cleveland; Beckton sued them for none payment of his report and Egton parish claimed they had not paid their share towards the poor rates. The Fosters put in many claims for damage to land and crops by the addition of sidings to the new shaft. By 1875 the shareholders voted to wind the business up, it being offered for sale the following year. Egton Estate further claimed the company had not paid the royalty dues and that by buying Glaisdale furnaces rather than building one on site breached their contract. South Cleveland tried to mine the stone until finally liquidating around 1879, the company dissolved in 1884. Although Esk Valley Mine had a history of around 25 years, much of that time it did not produce stone and men were employed simply to keep the water pumps working. Thomas Evans stayed in the manager’s house until 1889, getting involved with other local mining speculations.

Ref Egton Estate records at NRO, Whitby Gazette, British Transport Commission archive letters.